This story originally ran in Arkansas magazine, the quarterly publication of the Arkansas Alumni Association, in 2006 as the student newspaper, The Arkansas Traveler, celebrated its 100th anniversary.

On a February afternoon in 1948, two University of Arkansas students scurried over to the old Law School building near Old Main. Both of them worked for the student newspaper, The Arkansas Traveler, and were on the trail of a big story. One was a news reporter named Bob Douglas, who had come back to college after serving in the Navy during World War II. The other was a photographer named Robert McCord, who had started shooting pictures for the Arkansas Democrat at the age of 15 and was now in college contributing to the campus paper.

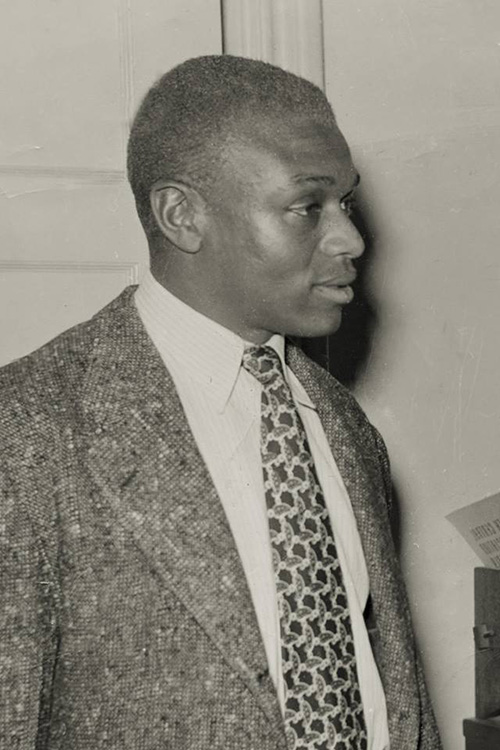

Earlier that morning, a car filled with four men had left Pine Bluff for Fayetteville, slowly covering the icy two-lane highways of central Arkansas and then wending over the Boston Mountains on U.S. Highway 71. Among the four was a young man named Silas Hunt, who wanted to enroll at the university.

Hunt, a native of Ashdown, Arkansas, had served in combat infantry during World War II and was wounded during the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he came back to Arkansas and finished his undergraduate degree at Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College in Pine Bluff, now called the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. With an undergraduate degree done, he wanted to enroll in the UA Law School.

Hunt was going to be the first black student to enroll in a traditionally white Southern university since the days of Reconstruction, perhaps the most historic event in the history of the University of Arkansas since its founding. The editor of The Traveler, Wanda Wassner, sent Douglas and McCord to cover the event for an “Extra” edition of the student paper, which ran photos and two stories, one about Hunt’s enrollment and one about reaction from students. The reaction turned out to be low-key but mostly positive.

“It didn’t result in any kind of good or bad reactions,” McCord said recently in an interview about the event. “Afterward, I went down to the house, to the Kappa Sig house to eat, and I was pretty excited about it and telling them, but everyone else was, ‘Oh, yeah? Uh, huh. OK.’”

One of McCord’s photos of Hunt with Robert Leflar, dean of the Law School, was picked up by the Associated Press and went worldwide.

“I don’t think I knew how big a deal it was,” said McCord, who now works for Arkansas Times as a columnist.

The coverage of Hunt’s admission to the University of Arkansas shows best the many roles that a college newspaper plays: a chronicler of campus events, a marketplace for student opinion, a reflection of the campus to the greater world, a laboratory for students to learn journalism skills, and a watchdog for the university community. Celebrating its 100th year of publication, the student newspaper on the University of Arkansas campus is still serving each of those functions.

The first student publication at the University of Arkansas came out in 1893. Julia R. Vaulx, a University of Arkansas student and later a long-time head of the university library, edited the Arkansas University Magazine, which changed its name to The Ozark in 1895. Primarily a literary magazine, The Ozark occasionally included stories of news events and successfully campaigned in favor of changing the name of Arkansas Industrial University to the University of Arkansas. It ceased publication in 1901. During the 1905-06 school year, the magazine was revived for a year under the name of The New Ozark by editor Brodie Payne, author of the university’s “Alma Mater.”

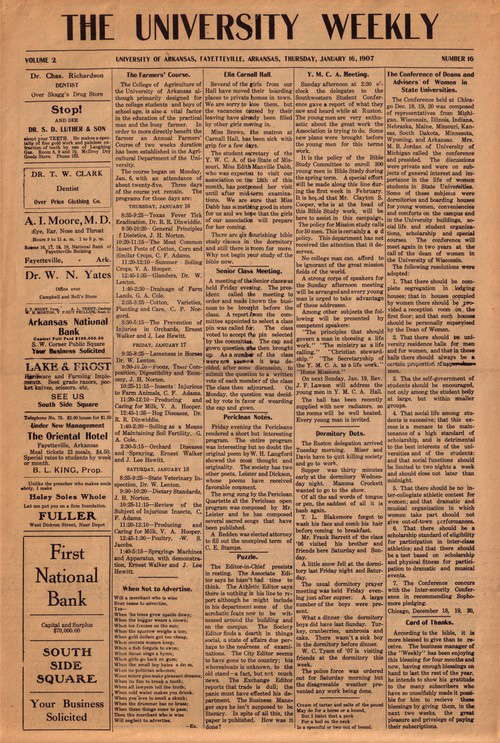

In the following school year, the first issue of The University Weekly was published on Oct. 10, 1906, with Joseph Othel York editing. York, a senior from Bellefonte, Arkansas, in Boone County, assembled a staff of about a dozen students to publish the paper through its first year. Published by the student body, single copies cost five cents, and year-long subscriptions cost a dollar.

The newspaper started as a five-column tabloid-size edition with a column of advertising down the left side of the front page, the rest of which was devoted to news of the campus. Front-page stories could include addresses by professors, notes from the residence halls, recounts of social receptions and sermons in favor of virtuous living. Page 2 included editorials, exchanges from other university papers, and various submitted announcements. Page 3 gave society and club news. Page 4 was reserved for sports. Editors generally kept this organization through most of the 20th century.

By 1910, the first history of the university referred to The University Weekly as having “made a place for itself by giving gossipy news from week to week and more or less full accounts of important events of university life.”

In 1920, the editors of The University Weekly considered adding a second edition per week, necessitating a change in the paper’s name. They proposed a contest, and about 30 names were submitted by students, including The Wild Boar, The Arkansawyer, The Pig, University Voice, Ozark Echo, The Pep, The Student Forum, The University Owl, Who-e-e Pig, and Razorback Grunts.

Students voted for The Arkansas Traveler by nearly a 2 to 1 margin. Both Septimus Elmo Kent and Robert Leflar had submitted the name of Arkansas Traveler, but Kent had submitted it first and won the prize. Leflar later wrote that the editors had put Kent up to submitting the name. Regardless, the new name stuck.

During the 1920s, The Traveler occasionally editorialized against the vices of the day: liquor, tobacco and objectionable dance steps such as the shimmy, the camel back and the scissors. Wrote one anti-smoking editor: “Ho, ye long, lank, sallow faced, short winded, weak hearted, yellow fingered, pimple faced cigarette fiends listen to this. Throw away that coffin tack, brush the ‘smokin’’ off your clothes, … grasp something solid with your nerveless fingers, straighten up your back and try to fix the apparatus in your think shop.”

In 1928-29, Mabel Claire Gold edited The Traveler. Her father had worked in newspapers and she had worked at the Fayetteville Democrat under the tutelage of editor Lessie Stringfellow Reed and publisher Roberta Fulbright. Gold wasn’t the first woman to edit the paper. Elizabeth Adams had the honors during the 1913-14 school year. Like Adams, Gold proved to be among the best editors up to that time and brokered no sexism on the paper. When the all-male UA Press Club held a stag party, she bobbed her hair and dyed it, donned a suit and tie, penciled in a mustache, and crashed the party almost unrecognized.

At the end of the decade, a “blanket tax” was instituted to pay for publishing the yearbook and newspaper. The Traveler moved its office from the third floor of Old Main to Room 107, added equipment including a couple of typewriters and tripled its press run.

In the early years, the student newspaper was often printed by one of the Fayetteville newspapers, either the Fayetteville Democrat or the Sentinel. Through the 1930s and 1940s, the Fayetteville Printing Co. printed The Traveler until the university bought its first printing press in 1949.

Walter J. Lemke, the founder of the journalism department, had lobbied for a university press from the moment he arrived on campus in 1929, but the Depression and decline of the university’s fortunes in the late 1920s and early 1930s precluded purchase of a printing press and left The Traveler itself “tottering on the steep edge of a financial brink,” an editor wrote. Within two years, though, The Traveler was back in the black and reporting a surplus at year’s end of $325, more than 10 percent of its annual budget. By the end of 1935, The Traveler and Razorback yearbook had put back $6,000 by 1935 to purchase a printing plant. Sidney McMath, president of Associated Students and later a state governor, had another idea. He proposed to use the money, which had come from student fees, to establish a student loan fund to supplement two existing student loan funds.

The Traveler editorialized against the change: “Back in 1930, the Traveler was provided with one second-hand Woodstock typewriter. That was the last equipment ever to be furnished to The Traveler office. Its other equipment consists of two scarred and ancient desks, a decrepit filing cabinet, and a rickety, nondescript affair full of pigeon holes that serves as a catch-all. There is nothing else. … Into this pleasing scene steps a politician who has made a spoils promise to spend the money in the publications reserve.”

A slim majority of the student body, however, approved the change in the publication reserve fund, once again postponing installation of a campus printing press. Lemke’s argument for a press was that it would save the university money compared with the cost of contracting private companies for printing jobs. His argument wasn’t lost on administrators, but the death of President John C. Futrall, the ouster of William Fulbright and then the advent of World War II prevented the university from installing a press.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor was barely a blip in The Traveler, which was focused strictly on campus events at the time. The paper published reaction from students and a photo of them listening to radio broadcasts in the student union, but the lead story was about the threat that the new governor posed to the university and its new president, J. William Fulbright.

Pretty quickly, though, The Traveler joined the war-time campaign, adding American flags to its nameplate, reporting on the status of UA students overseas and leading efforts to sell war bonds and donate blood. As male students went off to war, female students became leaders in the campus organizations, including The Traveler. Editor Helen Tidwell lamented the war-time shortages, especially when gasoline was rationed. The Traveler had sent copy to the printshop by way of the local taxi, but was forced to hire a bicyclist. “The Traveler may soon be advertising for a broken down horse and buggy,” she wrote. “Who knows?”

In December 1948, though, the university’s Publications Board forwarded a proposal by Pendleton Woods, president of the university’s Press Club, to install a printing plant on campus. The next spring, plans were announced to move the journalism department and student publications into Hill Hall. The plans included installation of a printing plant in the basement at a cost of $65,000, part of which came from the old student loan fund, none of which had ever been used by students but which had grown in the meantime.

On Nov. 11, 1949, the first edition of The Traveler came off the new university press with John Troutt Jr. as editor of the paper and Al Blake supervising the printing plant.

Across the nation and on the UA campus, the 1950s proved to be a quieter time, if stories in The Traveler are any barometer. In 1951, photographer Aubert Martin devoted several pictures to a rare football victory over the University of Texas, including cheerleaders, dazed Longhorn players and grinning Pat Summerall. The next year, the paper ran stories about the “panty raiders” who broke into sorority houses. The paper started a weekly photo feature called “Coed of the Week.” And in 1958, The Traveler sent a reporter and photographer to Fort Smith to cover the induction of singer Elvis Presley into the U.S. Army.

In 1952, publication was expanded from two days a week to four. The total number of pages per week remained the same, however, and the number of campus stories fell slightly as wire stories from United Press and the syndicated cartoon strip “Peanuts” were added in 1956. By 1958, editor Scotty Scholl announced the paper would print five days a week.

During the next two decades, staff members of The Traveler covered the campus and beyond during a stressful American period. Although the paper remained fairly conservative in its editorial stance through the 1960s, the news it covered was not. Protests against the Vietnam War, pitched battles for racial equality, censorship of student publications and campus speakers, and a swirl of political visitors including Richard Nixon, Ralph Nader, George McGovern and Barry Goldwater kept the paper full of headlines.

At the end of the decade though, The Traveler and the journalism department suffered their own calamity when Hill Hall caught fire. The first person on the scene was Skip Rutherford, then a student reporter for The Traveler. He had seen a woman standing in front of the building pointing toward smoke at the top of the building. Rutherford ran inside and up the stairs but stopped short of The Traveler doorway when it caught fire.

Crowds of students watched the fire burn into the night as Fayetteville firefighters tried to bring it under control. The Traveler staff, however, had a story to cover but no equipment for printing. Charles Sanders of The Springdale News stepped out of the crowd to offer his newspaper’s press. Editor Brenda Blagg marshaled her staff at nearby Futrall Hall and published a newspaper the next day.

In the early 1970s, a series of editors were fired or forced to resign by the UA Board of Publications. Profane language in the paper ignited more than one fuse, and editors suffered the wrath of a straight-laced journalism faculty. When the journalism department moved to the new Communications Center, now called Kimpel Hall, the staff of The Traveler remained at Hill Hall by choice.

Printing Services increased its press-startup costs in the mid-1970s, forcing editors to reduce distribution from five times a week to twice a week by the end of the decade. The number of pages published per week, however, went up as advertising increased.

Pay for the students who wrote, edited and produced the paper, though, remained almost laughable. Denise Beeber, an editor in 1984-85, recalled being paid “the princely sum of $15 a week” as a writer and a raise when she became editor. Now a news editor for the Dallas Morning News, Beeber said that working on the student newspaper taught her the value of teamwork and proved an invaluable way to learn the skills of interviewing people and writing and editing on deadline. She also learned just how passionate some writers of letters to the editor can be.

“We were sued by a prolific letter-writer,” she said, “who believed the paper, its staff and the university were conspiring to deprive him of his First Amendment right to free speech because The Traveler wasn’t publishing all of the letters he wrote to us.”

The lawsuit was eventually thrown out of court.

In 1991, The Traveler made news of its own when the paper inserted condoms in each issue of the last edition published before spring break. The editor, Ray Minor, and managing editor, Karina Barrentine, guided the staff in developing a package of stories about the dangers of the sexually transmitted human-immunodeficiency virus and the potential it might cause AIDS. The condoms, however, garnered all the publicity they could want and even more when the manufacturer later recalled the condoms because of potential defects.

During this timeframe, the university hired a professional director of student media to oversee the business operation of both The Traveler and the Razorback yearbook. Today, Steve Wilkes, a former Traveler editor himself, serves that role, and another former Traveler staff member, professor Gerald Jordan, serves as the faculty adviser to the paper.

Through the 1990s and beginning of this century, the publication schedule of the paper was slowly expanded again to four times a week, and an online edition of the paper was added. The pay is still bad and the hours too long, but letters to the editor keep coming in over the transom, showing that The Arkansas Traveler remains a central force in lives of students on campus and beyond.