This interview with Betty (Hayes) Davis first appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Flashback, the historical journal of the Washington County Historical Society.

Davis organized a family reunion for her many nieces and nephews in 2011 and in researching her family history tracked down many photographs, articles, documents and obituaries related to her ancestors. When she brought the extended family back together, some members of whom had never met each other, she said that they arrived in Fayetteville as splinters, but by the end of the weekend, they had become a board. The following article includes excerpts from an interview conducted with her on June 6, 2012.

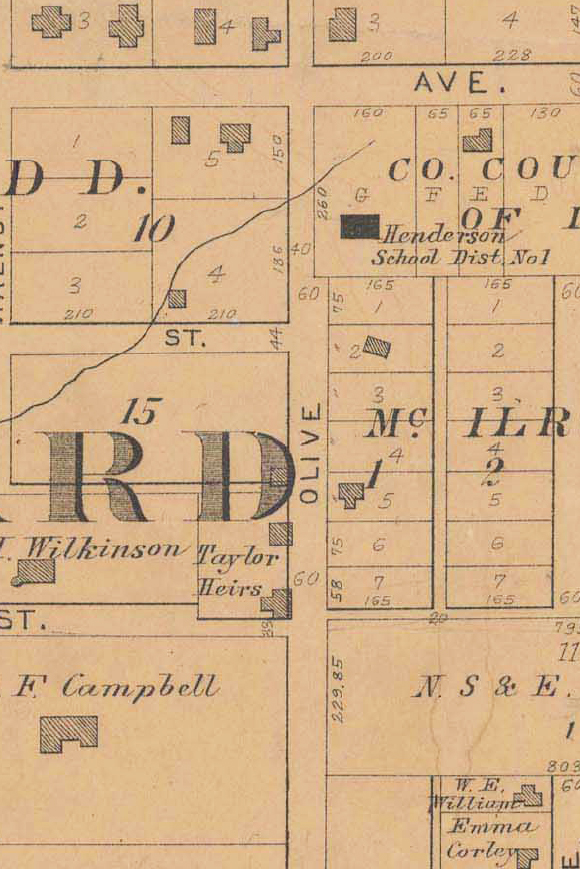

Betty Davis’s great-grandparents on her mother’s side were William “Squire” Taylor (about 1845-1921) and Tabitha Marshbanks (about 1850-1930). They had been slaves prior to the Civil War but were freed during war. Davis said that family lore indicated her great-grandparents moved from the Farmington area to Fayetteville during the Civil War and bought property along present-day Olive Avenue with money provided by their former master.

Betty: “Now Squire and Tabitha, I still don’t know how they got to Farmington. Some came here with owners. See we’re talking about a time before they became freemen. Some were brought here and released here. … But they got to Fayetteville from Farmington.

“We know that Squire and Tabitha were in union before they were allowed to buy a marriage license. I have a copy of the marriage license. They were together before that. Back then, when a slave took a woman for his wife, they had to do it in the old system: ‘jumping over the broom.’ Whether they jumped over the broom, I have no idea. I don’t know how they managed.”

Squire and Tabitha were officially married on Nov. 6, 1879, by then already involved in the Fayetteville community, helping organize the St. James A.M.E. Church.

Betty: “Now my great-grandfather is listed as the first Sunday School superintendent. You know before they built St. James, they had a church on Rock Street. Now Squire and Tabitha came here about 1861 or 62. And that was about the time that the community was trying to form a religious entity. So they had Sunday School first before the built St. James.”

Betty was born five years before her great-grandmother Tabitha died and recalled her last years.

Betty: “My great-grandmother, she was alive the first five years of my life, and because she was sort of bedridden, … we [Betty’s mother, Betty’s aunt and Betty herself] were there constantly at her bedside, and when she got to the point where she would say no to them about taking medicine, they would give it to me, and I would go in and say, here, take this, and she would take it.”

One of the mysteries of her research into her family tree is her grandmother, Susan, who was listed as a Marshbanks at the time of her marriage to Betty’s grandfather, Joseph Manuel, on Jan. 7, 1886.

Betty: “We have been looking for the Marshbanks because the confusing thing is that Tabitha was apparently a Marshbanks. Susie, her daughter — who we always thought was a Taylor — when she married my grandfather, she was still listed as Marshbanks.”

In the 1880 Census, Susan Marshbanks is listed as a step-daughter of William Taylor. Regardless, Betty had little luck finding out more about Susan Marshbanks. She was also curious about the appearance of Susan, suggesting that Susan looked as though she might have American Indian as part of her heritage.

The property that William and Tabitha Taylor purchased on Olive Avenue eventually became home to the Taylors’ extended family. Betty said that her grandparents began offering their children part of the property and construction of a two-room house whenever one of them married. By the time she was born, there were four family houses in the 300 block of Olive Avenue.

Betty: “At 309 next door to where I was born, that was my Uncle Ralph’s house. When he married, they gave him the lot and built two rooms. Well, he didn’t stay there because he went to St. Louis and never came back.

“Then — when my mother and father married — they gave Daddy and my mother a lot, built the first two rooms, and then Daddy put five more rooms on.

“At some point, Daddy decided that he needed to make more money for the children’s school clothes, so he went back to my grandfather, and said he wanted to buy a piece of property. He asked … my grandfather if he would sell him an extra lot. He said I’ll not sell it to you, but I’ll give it you.”

So her grandfather, Joseph Manuel, gave her father an extra lot across the street, and her father planted strawberries on it.

Betty: “Now that crop, his strawberry crop, was very lucrative. I have a little piece of paper where he had recorded the money he got for his strawberries back in the ’20s. … He made $300 that year, and I think that’s awesome.

“Piggly Wiggly, I didn’t even know there was a Piggly Wiggly back then, and that’s who was buying his strawberries. My mother would always say that my daddy never kept a penny. … He would give it to [my mother] to buy the children’s school clothes and supplies.”

When Betty turned 6 years old, she began attending Henderson School, less than a block from her house.

Betty: “I guess I was six. The bell would ring, and I would start sprinting and get in line. We always had to line up to go into school. And I was only about a half block away. Living so close, I didn’t think I needed to take a note for being late. I just liked the idea of hearing that bell and knowing, woops, I got to go! Be there in time to get in line and march into school.

“At Henderson, you went from one room to the other, depending on, you know, what grade you were in. One room would simply change classes by the front row going to the back. Sometimes, depending on what grade you were in, you might have gone from one room to the other. It was just shifting between those two rooms for eight grades.

“We were lucky to have two rooms and outhouses,” she said laughing.

The brick building that housed Henderson School still stands, although today it has been enlarged and is used as a private residence. Betty said the two rooms that comprised the school are just as they were when she was a student. Henderson quit serving as her school when a new school, Lincoln, opened on Willow Avenue in 1939.

Betty: “Henderson closed in 1939 as a school. They had built a new school on that corner where the projects are. [On the east side of Willow Avenue between Rock and Center.] So we marched to that building. We marched and we sang. The principal’s wife, who taught also in that school — she was a music major — and she wrote this song for us to sing:

“Old Henderson School is too old for its age,

Since the new Lincoln was built.

Old Henderson School is just too old for its age,

Since new Lincoln was built.

Seventy years without stumbling, tick, tock, tick, tock.

It’s lights never trembling, don’t stop, don’t stop.

But it’s closed now, never to open again,

Since the new Lincoln was built.”

During her first eight years of school, she had Herman A. and Hazel G. Caldwell as teachers. They moved to Texarkana, and her teachers changed for ninth grade at Lincoln. She recalled the principal’s last name as being Radcliff, and her teacher that year was Juanita Parker, the oldest daughter of Otis and Anna Parker.

Betty described the black community of Fayetteville when she was growing up as consisting of four communities. The black families who lived near her on Olive were known as living on “The Hill.” In addition to her own relatives, Russell and Pearl Bly lived nearby as well as at least one other family.

Betty: “The Hill. That’s where I lived. There was a time, I was told by my parents, there were two other black families that owned property up on Olive. One was the Bly family, and they owned the property next to the school, and at one time — this is true — there was some people in Fayetteville who wanted to live up here but they didn’t want to have black neighbors. They offered exhorbitant money to buy us out. None of my family would sell. The Blys sold out and moved down in the Hollow. My family just decided they liked where they lived. Only our family lived up here.”

The other three communities included families who lived in the Hollow, the Valley and Red Hill. The Hollow was and is an area along Willow and Washington avenues, roughly bounded on the north by Spring Street and on the south by Huntsville Road. To the south where Washington and College avenues run into 15th street, the black community was known as the Valley, And last, a small group of black families lived on the hill to the east of the intersection of College Avenue and North Street, an area known as the Red Hill community.

Betty: “The Valley, when I was growing up, consisted of the area beyond [Huntsville Road] down through that area toward 15th street. That was called the Valley. That’s where there was a confluence of black people who lived down there. Otis Parker and the Hoovers and the Rogers.

“If you were to continue on Willow Street. Anyone who lived on Willow Street this direction, up this way, actually lived in what they called the Hollow, and they still call it the Hollow.

“There was a community known as Red Hill. That was where there was black families. There was a small community of blacks out there, four or five. Blackmon and the Dowells and their folk, it was their community.”

Betty described a duality in the community regarding the relationship between races. During the 1920s and 1930s while she was growing up, Fayetteville abided by the laws of Arkansas that tried to maintain separation of races. She recalled not being able to go to the movie theaters in town, except that occasionally, special dispensation was allowed for a movie such as “An Imitation of Life.” Yet Fayetteville was one of the few towns in the region with a school for blacks, albeit only available through the eighth or ninth grade. It was also one where some job opportunities existed, although again the types of jobs available to blacks were very limited. Of her own family, her uncle Chris Manuel graduated from Philander Smith College but could only find work as a bootblack. Meanwhile, her aunt worked as a caterer, perhaps the height of jobs to which African American residents of Fayetteville could aspire during the 1920s and 30s.

Betty also explained that, today, a lot of people are still uncomfortable when hearing racist language and try to soften it by using euphemisms.

Betty: “I hear people now, they won’t say the word ‘nigger.’ They politely say ‘the N word.’ And it cracks me up. You know why? If you know what it is, how much can you sweeten it.

“But let me tell you it was a word that never resonated with me. Never. Because early on I remember — I can’t remember how young I was — my mother sent me to Graham’s grocery store on the corner of Olive and Maple. And on the way there, these children were hiding behind the house and that’s what they were taunting me. But I was always told to ignore it so I kept walking. But my mother said let me know whatever happens in your life. She wanted to know everything.

“So when I got home and said, ‘Momma,’ she said ‘What baby?’ ‘There was some children hiding … and they were calling me a nigger.’ She just came and said, ‘Well, are you one?’ And I said, ‘Oh no.’ ‘Then why would you let it bother you?’

“My mother diffused any hurt that word could have.

“I said I had two very strong women in my life. One was my mother, and the other one was Susan [Chadick]’s mother [Ruth Ellis Lesh]. My mother was my positive force at home, and Susan’s mother was always a positive force in my community. So the things that other people grew up having impact their lives didn’t impact mine.

“We were taught to be a part of the community. … I’ve walked into many lions’ dens, but like Daniel I walked out again.

“If you go through life being afraid of what might be, you’ll always be afraid.”

Like many students from the African American community, when Betty finished the nine grades of school offered to blacks in Fayetteville, the only way she could continue her education was by leaving Fayetteville. Fayetteville High School was segregated and only permitted white students until 1954. Many black students who wanted to continue their education attended high school at Fort Smith, but Betty’s mother, Clara, found out that the school was not accredited, and she wanted Betty to be able to go to college after high school. So her parents sent her to attend Sumner High School in St. Louis, where she could live with her uncle, as had two older siblings.

Betty: “I always knew that, by hook or by crook, I wanted to go to college. … When I finished Sumner in St. Louis, I had a scholarship to go to college. I would have been one of the first black students to go to St. Louis University. In 1946, my mother died in August, a month before I was to go to school. That was the end of my scholarship. I was left with bills to pay and the house.”

She returned to Fayetteville to take care of her family’s estate and went to work locally.

Betty: “There was an Army colonel — Col. Dingler and his wife — came back to Fayetteville. She came to the house to see my mother, not knowing that she had died. … When she found out my mother was dead and found out that I was the last of her children, she wanted to know what I was going to do with my money. I announced to her that I’m working now to make enough money to go back to college. She looked at me and said, my dear, you will never make enough to go to college.

“To make a long story short, she invited me to come over to Mount Nord where she and the colonel were staying.”

It took three visits with the Dinglers before they had talked her into joining the Navy WAVES, the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. She would spend two years serving in the WAVES, and the government would then pay her tuition.

Betty: “I really knew that made a lot of sense, so that’s what I did. That gave me the GI benefits to go to school.”

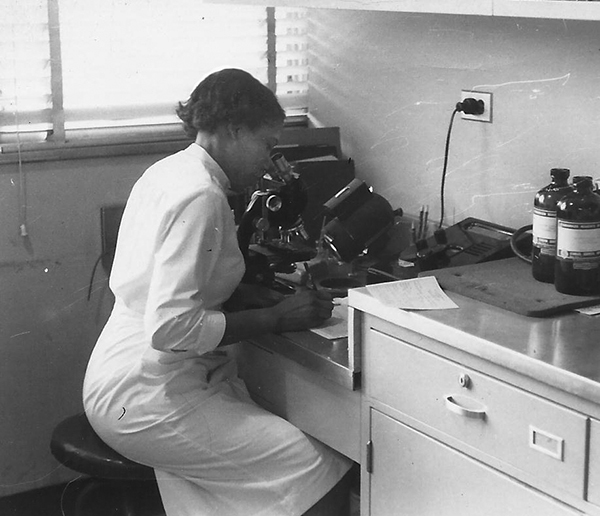

She chose New York University after her tour of duty was finished.

“I was a medical technologist, and I worked at NYU. I worked at NYU before I was a student. … I always tried to put building blocks together. When I got out of the Navy, I took a portion of my money and I went to a medical tech school because I had the basics in the Navy. I got my certificate. That gave me a chance to walk into someone’s medical facility and go to work.

“Had I done it the other way and gone into a college immediately, I would have to find a job. They wouldn’t give me a decent salary. I went to work at NYU after I had used some of my money. And the day I went to work, I was entitled to 12 free credits. So I went to school and worked at NYU.”

While in New York, Betty also met her future husband, Bill Davis. They married and she expected to stay there for awhile because Bill had no desire to live anywhere else.

Betty: “I was gone almost 40 years but I came back. I always knew I would. My reason for leaving was I knew I wanted to go to college and find a career.

“Actually, my husband brought me back. He said his thing was: ‘Don’t ever ask me to leave New York. I was born here; I was raised here; I intend to die here.’

“Well, I thought that’s no big thing, I can always go to Fayetteville to visit. Coming up to our 25th wedding anniversary, he walked in one day and said to me: ‘How would you like to go to Fayetteville?’ Twenty-five years and he had never seen this place. I said, who would want to go to Fayetteville to celebrate an anniversary alone. He said, ‘Who says you’re going alone?’ He brought me back.

“He just didn’t tell me that he had a medical problem. He worked for a medical group and there were 13 doctors there. And one day, he and the director of nurses had lunch together, and he told her he was going to bring me home to get me settled before he had to leave me. But he never told me that, and I never heard it until she wrote me a letter after I buried him and told me that he had told her that.

“I thought that was really pretty unselfish of him.”

When they moved back, they initially lived on Township Road.

Betty: “He got me back. I got settled. I remember one day, Polly Baker … came to the house and said, who is that man talking to Bill. He’s from a company that puts in security systems.

“She said, ‘Bill you don’t need a security system. This is Fayetteville.’

“He looked up and said, ‘But I want it darling.’

“When he left me, he left me secure.”

Betty later lived in Arkanshire for 6 years but decided she “didn’t need the constant nurturing.” She moved from there to a house on Olive Avenue that she rents from Susan Chadick, barely a block from the neighborhood in which she grew up. The four houses in which her extended family lived no longer stand, but two stone steps that led down to one of the houses are still visible along the streetside.

Betty: “You know, I still say that I had people who made a way for me. They made my path easy.

“You have to pass it on.”

The family reunion that she organized earlier this year was her way of passing on her family’s history.

Betty: “I said I had a dysfunctional family. Being the last of that dysfunctional family, it was my desire to bring them together. I tell people that when I got them together at Mount Sequoyah, we had some splinters, but when we left we had a board.

“I think that they were ready for it. … They were just enrapt. And every time I told a story, there was a hush.

“So this is what I was all about, bringing these poor souls together. Giving them a sense of pride. You came from some solid people. Tabitha and William were solid people.

“To me, it’s been a great life. That’s why I feel I need to pass it on.”