NOTE: This article first appeared in the Spring 2012 issue of Flashback, the quarterly historical journal of the Washington County Historical Society. An abbreviated version was also edited for the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

The violinist and composer Ferdinand Frederick Zellner lived in Fayetteville for a little more than a decade and wrote a piece of music, the “Fayetteville Polka,” believed to be the first Arkansas composition to be published as sheet music. His life as an educator and musician, though, has remained obscure.

Zellner was born in August 1831 at Berlin, Germany, then part of the Prussian empire. His brother Willhelm Emil Zellner was born two years later, also in Berlin. In at least one census record, Ferdinand Zellner reported not knowing the names of his parents. According to family lore, though, the brothers came to America together, in part to avoid military conscription into the Prussian army.

However, Ferdinand Zellner also came to the United States in 1850 for vocational reasons, as a violinist with the orchestra that performed and toured the country with the Swedish nightingale, Jenny Lind, herself brought to America by the great impresario, P.T. Barnum. Lind was born and reared in Sweden, but mostly trained in France and Germany, learning opera and becoming one of Europe’s best-known singers. Barnum had never heard her sing, but he had heard about the size of her audiences. He proposed a contract that would bring her to America for a set number of performances.

Other similar offers had been made to Lind, but the terms of Barnum’s contract were less demanding and more lucrative to Lind, who wanted to raise money to create a musical academy for girls in Stockholm, Sweden. Despite Barnum’s reputation as a showman who occasionally traded on the public’s gullibility, Lind accepted the contract and came to America, arriving at New York City aboard the steamer Atlantic on September 1, 1850. Waiting for her and her orchestra was a crowd of more than 30,000 people, spread along the docks of the New York harbor.

The company performed in New York City, Boston and Philadelphia before touring the southern seaboard and Cuba. The entourage then traveled across the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans, where the company performed 12 concerts.

Leaving New Orleans on March 10 aboard the steamer Magnolia, Lind and her company of musicians traveled up the Mississippi River to perform at Natchez on March 12. The troupe stopped briefly in Memphis on March 14 for a midday concert and then reboarded the Magnolia to continue up the Mississippi to St. Louis for several concerts. Eventually, they made their way up the Ohio River, returning to New York.[1]

The factors that affected Zellner’s decision to come to Arkansas when Lind returned to Europe are unknown. Perhaps he liked the view of eastern Arkansas on his trip up the Mississippi River. Perhaps an entourage of Fayetteville residents went to Natchez, Memphis or St. Louis to see one of Lind’s concerts, met Zellner by happenstance and persuaded him to come to Fayetteville. Perhaps, like many emigrants to the Americas, he simply moved west in search of a new start. Regardless, he moved to Fayetteville by 1852 and filed papers in Washington County that year showing his intent to become a United States citizen. Family lore says that Zellner and his brother, Willhelm Emil Zellner, moved to Fayetteville at the same time.

Sometime soon after arriving, Emil Zellner took up the cabinet-making craft, while Ferdinand Zellner began teaching music at the Fayetteville Female Seminary. One of Emil Zellner’s granddaughters, Julia Zellner Thompson, described Ferdinand Zellner: “I remember him as a very small and slender man, soft-spoken and quite courtly in his mannerisms. He wore a Van Dyck beard and his appearance was very much like that of Kaiser Wilhelm.”[2]

The seminary was established in 1839 by Sophia Sawyer, a missionary to the Cherokee nation. She initially taught in southern Tennessee and northwest Georgia but traveled west with Cherokees when they were forced to leave their traditional homeland and resettle in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Sawyer was closely associated with the Ridge and Boudinot families, members of the Treaty Party who signed a treaty with the federal government, agreeing to move west. Once in the Indian Territory, though, a faction of Cherokees that blamed the forced removal on the so-called Treaty Party took revenge, killing the patriarchs of the Ridge and Boudinot families. Because of the civil strife within the Cherokee Nation and the perception of continued danger in the Indian Territory, the Ridge family and Sawyer moved to Fayetteville.

Sawyer’s school grew in reputation and drew students from across Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas and the Indian Territory, as well as occasional students from the east. In the early 1850s, Sawyer hired Zellner to teach music. The school had employed other music teachers when possible, but music was usually an adjunct subject taught by a teacher who happened to have some musical knowledge in addition to traditional subjects. When the school first taught piano, the lessons were strictly provided as theory because the school had no piano for practicing. By the time that Zellner, however, the school had received a piano from a family in exchange for education of their daughter.

Sawyer died of tuberculosis in 1854, and her estate was willed to the American Missionary Board, which had never provided financial support for her school but from which she felt a moral support. The Missionary Board in turn sold the school to one of the teachers, Miss Mary T. Daniels of Fayetteville, who sold a half interest to another teacher, Lucretia Foster Smith, who became principal of the school. Zellner continued his teaching of piano and violin.

Along with his teaching, Zellner began writing music, creating songs based on the popular styles of Germany with which he had grown up. His first published composition was titled “Fayetteville Polka” in honor of his adopted home but also with a nod to his native home. The “Fayetteville Polka” is believed to be the first composition published by an Arkansas writer. The well-established publishing house of Balmer & Weber of St. Louis printed the “Fayetteville Polka,” and Zellner began a long friendship with Charles Balmer, one of the principles of the firm.

The genre of music known as polka originated in Bohemia and spread west across eastern and central Europe into Germany early in the 19th century, and then to America via German immigrants such as Zellner. Polkas hit the height of their popularity during the mid-19th century, both with audiences and composers. Zellner dedicated his polka to one of his students, Katy Smith. As a young girl, Smith was voted Queen of May in 1852 and crowned in Fayetteville’s McGarrah Grove, next to the campus of Arkansas College.

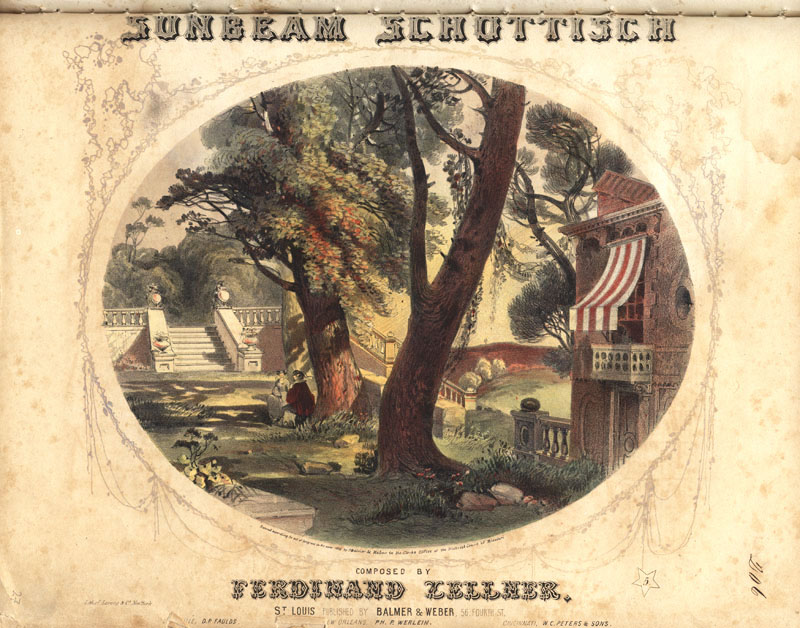

Zellner was only 24 years old at the time the “Fayetteville Polka” was published in 1856. He was described as having black hair and hazel eyes and as standing 5 feet 11 inches. Whether the dedication to Katy Smith indicated a romantic attachment on Zellner’s part is difficult to ascertain. In the same year, she married Clinton Yell, the only son of the then-late Archibald Yell, the state’s first U.S. representative and its second governor. Zellner wrote another work, “Sunbeam Schottisch,” that was published by Balmer & Weber the same year, with additional copies also published in Louisville, Ky.; New Orleans, La.; and Cincinnatti, Ohio. “Sunbeam Schottisch” is a bright, swaying-paced tune that sounds like it should be the piano soundtrack to a silent movie. The schottische is another folk style that came out of Bohemia during the 19th century and became fused with American ragtime at the turn of the 20th century.

Zellner’s facility with musical instruments, however, did not extend to voice. His lack of vocal teaching prompted some criticism by girls attending a cross-town school that had been started by the Baptist educator, T.B. Van Horne. The Fayetteville Female Institute had a vocal instructor, a Miss Corwin who was a niece of Ohio Senator Tom Corwin, and she “could sing to ‘beat the band.’”[3]

Criticism of Zellner, however, also appeared to be rooted on some occasions only in his ethnicity. Some of the families of English and Scottish descent took a dim view of the immigrants from Germany and Austria. During the 1850s, Fayetteville’s population swelled, and part of the growth was fueled by immigrants who came from northern states and several foreign countries. In 1860, Zellner lived in a boarding house with 18 other people, including people from Iceland, New York and Massachusetts. Members of the Freyschlag family, who were also from Germany and had moved to Fayetteville much earlier, also taught at the Female Seminary and were disparaged by some members of the community. Although issues such as these bubbled in Arkansas, they never boiled over in the way that the question of slavery and secession did.

In 1861, when the state elected delegates to a convention to consider secession, sentiments in Fayetteville were strongly in favor of remaining in the Union. Although the region couldn’t be described as favoring abolition, both Fayetteville and nearly all of the mountainous part of northern and western Arkansas elected pro-Union delegates to the convention to consider secession, and they prevented Arkansas from seceding at their first meeting in March 1861. After the attack on Fort Sumter, S.C., however, the sentiments of the delegates swayed in favor of secession.

During the latter part of 1861 and early 1862, Fayetteville became a staging ground for Confederate forces that were forging allegiances with the Indian nations to the west and anticipating the possibility that Missouri might secede as well. Many of Fayetteville’s young men joined Confederate companies as they were organized. Zellner’s brother, William Emil Zellner, may have served in the Confederate army, but Ferdinand Zellner does not appear to have served on either side, and he later made statements indicating that he remained loyal to the Union.[4] His grand-niece said, “Ferdinand had the more gentle soul of an artist and he did not favor the militaristic life which was then prevalent in Germany. His life revolved around music and he wanted the freedom in which to practice his art.”

Confederate forces handed the Union its hat in the first major battle of the Trans-Mississippi at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri. The Confederate forces, however, did not press their advantage but instead retreated to Arkansas. With them came Fayetteville’s first casualties, four Confederate soldiers who were buried at Mount Comfort Cemetery.

As Union forces regained strength in early 1862 and pressed south, Confederate Gen. Benjamin McCulloch ordered his troops at Fayetteville to burn all buildings of military value in Fayetteville as well as vacant buildings. The buildings of the Fayetteville Female Seminary avoided being burned during this initial conflagration, but most of the mercantile and dry goods stores on Fayetteville’s square were burned, and the rival Fayetteville Female Institute, which had been turned into an arsenal, was also set afire to prevent its stores from falling into Union hands.

Union troops under Gen. Curtiss arrived in Fayetteville in late February but soon withdrew and moved north close to the Missouri line.

Less than a week after they had left Fayetteville, the Confederate troops came back through headed north for the Battle of Pea Ridge. The Union troops held sway at Pea Ridge, the largest battle of the trans-Mississippi, and the Confederates retreated south of the Boston Mountains. Although Fayetteville was recaptured by the Union forces days after the Battle of Pea Ridge, Union commanders did not believe the city could be held and withdrew again. Over the rest of the year, both forces traded occupation of Fayetteville.

Fayetteville residents tried to carry on with daily life as best they could.

The Fayetteville Female Seminary continued to provide education as it was able. Ferdinand Zellner purchased the buildings and grounds of the seminary from Lucretia Foster and Mary Daniels in 1862. His presence in Fayetteville during this period also augurs against the likelihood that he served in the Confederate army. After the Battle of Prairie Grove in December 1962, the main building of the seminary was used as a hospital, as were many other homes and buildings in Fayetteville. Sometime later, though, the two main buildings of the school burned, and at least one report indicated the fire occurred during the Battle of Fayetteville on April 18, 1863.

The ebb and flow of Union troops, Confederate forces and guerrilla groups without allegiance caused residents on both sides to seek safety away from the border region. While Confederate-sympathetic families fled to Texas, those sympathetic to the Union left headed north to Missouri when circumstances and passage allowed. Sometime relatively soon after the Battle of Fayetteville, Zellner and other residents of Fayetteville left the town for safer situations. “My desire is, like theirs to find a place, which we can call our home once more, a place of which we have been so ruthlessly deprived at the very outset of this unholy rebellion,” Zellner wrote later.[5]

Initially, Zellner settled with the Tebbetts family, which had left Fayetteville earlier and settled a farm outside of St. Louis. The farm was described as comprising more than a thousand acres. The family began calling the farm “Exilia” as it became a haven and stop-off point for other refugees who left war-torn Arkansas for safer environs. Friends from Fayetteville such as the Baxter and the Graham families visited the Tebbetts family, and Zellner joined the milieu at Exilia temporarily before moving into St. Louis to begin teaching music again.[6]

During that same year, the exiles began planning a trip to California. Robert Graham, who had founded Arkansas College in Fayetteville, was solicited to establish an educational center at Woodland, California. To many living in the strife-torn border states, where divisive political sentiments and potential physical harm were the constants, the state of California, far removed from the war, represented a chance to escape the maelstrom of the Civil War. In January 1864, Zellner agreed to join the group and to take charge of the department of music at the California school, which he described as the Young Ladies’ Seminary.

Zellner moved from Exilia to St. Louis while the plans continued so that he could resume teaching private lessons. Jonas Tebbetts wrote that Zellner at first met with little success, so much so that he moved from his initial place of lodging to a boarding house “where his expenditures would be met by his income,” a move that Tebbetts recommended. The boarding house was at the corner of 12th Street and Olive.

In June, Zellner’s plans for a new life came perilously close to disaster. On June 1, 1864, Federal officials arrested him and several other residents at his boarding house. They were taken to the Gratiot Street Military Prison and charged with being members of a secret society plotting the secession of Missouri.[7]

Friends of Zellner came to his aid immediately, protesting that he had been a Union supporter. Charles Balmer of Balmer & Weber, the publishing house that brought Zellner’s compositions to print a decade earlier, was among the first to hear of Zellner’s arrest and spread the word. Both he and Judge Tebbetts wrote letters on June 3 to Col. J.P. Sanderson, the provost marshall general at St. Louis to seek favor for Zellner.

In a hastily written note, Balmer told authorities that Zellner had assisted at charitable events such as a recent benefit for the Sanitary Fair, events at which he provided his help for free or had given his own money to the cause: “These occasions together with his other bussiness [sic] have kept him busy enough & would have hardly left him time to meddle in other affairs.” After noting Zellner’s association with “strong Union Men,” Balmer added a post script: “I would further state that he is entirely depending on his music lessons for a living, his scholars being amongst the best families of the City & there fore bge [sic] you will make all due allowances in the matter.”

Balmer’s letter was joined by one from Tebbetts on the same day:

“Zellner has never been engaged in the rebel service and I always knew him as a Union man at Fayetteville after the commencement of the rebellion and while engaged in my family as a music teacher. I have known him intimately in the social relations of private life. He is a man of integrity & worth and if words & actions mean anything, he is and has been a Union man.”

Tebbetts himself was known to many of the Union military in Missouri for his staunch support of the Union while he lived in Arkansas and for being arrested by Confederate Gen. McCulloch on charges of treason. The weight of their letters was joined by a heftier one on June 4 from Judge Barton Bates of the Missouri Supreme Court, who had gotten to know Zelllner during the past year. Wrote Bates:

“I desire to state for the benefit that I became acquainted with him since fifteen or eighteen months ago in St. Charles County where he was then residing at the house of Judge J.M. Tebbetts.

“He was understood to be a Union refugee from Arkansas. I met with him occasionally and had conversations with him at different places in the neighbourhood.

“Last winter he came to St. Louis and since the present (March) term of the Supreme Court at this place, I have occasionally met him casually on the streets and upon my earnest invitation has visited me several times at my room in the Court house.

“From my intercourse with him I esteem him a very moral intelligent man of thorough loyalty, and if my testimony to that effect can be of any service to him, I will be ready to give it at any time.

“As I do not even know the charge upon which he is arrested, I cannot of course express any opinion about it.

“I can be found at almost all times at my room in the Court house.”[8]

Zellner was released from the military prison on June 4 after posting bond of $1,000 and making a statement to the authorities. The statement, which appeared to have been written in someone else’s handwriting, said that he was living in Fayetteville at the time the war broke out. “I didn’t believe in the so called Southern Confedracy [sic]. My Sympathies was always been with the north. I belong to no secret society. I took the Oath of Allegiance to the US in the summer 62 I think. … I never was in the Reble [sic] Army.” Upon release, Zellner was required to stay within the Department of Missouri, report for trial when called, and report weekly by letter to the office of the provost marshall general.[9]

A month later on July 7, Zellner wrote to Sanderson, the provost marshal general, to ask that he be released from his bond so that he could go west with the Tebbettses and Grahams to California: “I would desire, and hereby petition you, to be, either released from said obligations, or have the privilege of moving to the State of California and report there to the Officer in command. … I take occasion here to say, that I always have been, and ever expected to be, a supporter of the Government of my adoption.” [10]

The next day, Sanderson issued a letter requesting Zellner’s release from his bond. He wrote that “Zellner alleged that, whatever objectionable conversation or association he may have, justly subjecting him to suspicions of disloyalty, he never was in any way a secessionist or sympathizer; but, on the contrary, always an unconditional Union man.” Zellner was ordered released from his bond on July 11.[11]

By August, Zellner was in New York City to join the Tebbettses and Grahams to board the steamer Northern Light for the long trip to the Isthmus of Panama. The Tebbetts’ daughter, Marian, described the Northern Light, one of Vanderbilt’s liners, as a “miserable old boat.”

“The boat was dark and crowded and smelly,” she wrote. “One’s nose took a chronic uplift because of coming across chloride of lime saucers set at odd places. One had to wait for experience to teach him the difference between Atlantic and Pacific steamers.”[12]

That experience would come soon enough, but the group first needed to get across the Caribbean. Although the fighting of the Civil War had begun to turn against the Confederate forces, the steamer would have to pass through enemy waters off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. While crossing, the passengers caught sight of another ship shadowing their movements, staying within contact but not approaching. The Confederate ship Alabama had successfully attacked other Union boats in the same latitudes, and Marian Tebbetts expressed consternation that their small steamer might be attacked. As it turned out, the shadowing ship proved to be the federal gunboat Powhatan, which was acting as an escort to the Northern Light. When the group reached the Isthmus of Panama, the entourage enjoyed the markets of Aspenwall (Colon) and then took the train over the isthmus to catch the steamer Golden City, a dramatically nicer boat than the Northern Light.

Marian Tebbetts described the Golden City as being “clean and white and big, every piece of brass ablaze with polish, every sailor in white linen and everything run in the order of a first class hotel.”

Upon landfall at San Francisco, the entire Arkansas party took rooms at the Lick House and remained several days before taking the steamer Yosemite up the Sacramento River to Woodland for Graham to see the prospective school. The school at Woodland proved impractical, and the group moved on to Santa Rosa, where another school was reported to need teachers. Graham and his son, Alexander, opened a school in the city’s “big, awkward, redwood building.” A professor Fouch also taught, and Zellner took charge of the school’s music department.[13]

Although the Santa Rosa school proved a financial success, it fell short of Graham’s expectations, according to Marian Tebbetts. Meanwhile, her own mother and father were debating whether to stay in California or return to the east. The Grahams, too, wanted to return east but couldn’t afford the expense yet. Zellner, however, was planning to stay.

On March 1, 1866, he married Penelope “Neppie” Cocke, then 17 years old.[14] Born in 1849, she was the fourth daughter of William and Frances Cocke, of Jackson, Missouri, just northwest of Cape Girardeau. Prior to 1860, the family moved to Santa Rosa, California, where her father was worked as a farmer. Neppie Cocke only lived two years after her marriage to Zellner, dying Aug. 9, 1868, at age 19.

By 1871, Zellner began teaching at Pacific Methodist College. The college opened at Vacaville, California, in 1860, but its operations moved to Santa Rosa in 1870, at which time the college had 111 students. That number grew to 165 by the next semester. Zellner was listed as professor of music.[15]

The wider civic amenities of the bay area allowed Zellner to reconnect with fellow immigrants from his homeland. In December 1872, he was nominated for sergeant-at-arms for the Austrian Benevolent Society, which met in San Francisco.[16]

According to the San Francisco Morning Call, Zellner married Olive Jeanette “Jennie” Beam on July 1, 1874, in Santa Rosa. She was only 17 years old when they married, 24 years younger than Zellner. Beam was born in California in 1857. Her parents were Jeremiah Beam and Mary Logan Beam.[17] Her father was from New York and worked as a farmer, a cabinetmaker and furniture dealer during his life. He moved to Arkansas by the late 1830s and married Mary Logan on Nov. 11, 1839, in Crawford County. Although they had one child, David, in about 1846 while still living in Arkansas, they moved to Sacramento County, Calif., before Olive Jeanette was born in 1857.[18]

In California, Jeremiah Beam worked initially as a farmer and listed $4,000 worth of real estate and $5,000 worth of personal estate. The Beams moved to Petaluma Township in Sonoma County, Calif., sometime after 1860 and by 1870 were within Santa Rosa, where they would have come in contact with Zellner if not sooner.

Ten months after their marriage, Ferdinand and Jennie Zellner had their first child, a son, on May 1, 1875, according to the Russian River Flag, the newspaper of nearby Healdsburg, Calif. This first son appears to have died as an infant though and was not listed in the 1880 census.

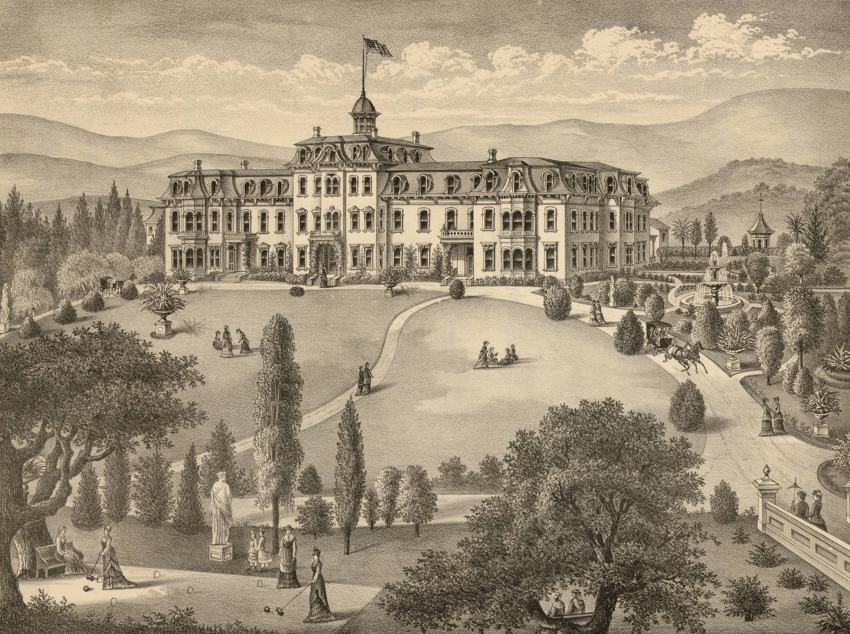

In 1876, Zellner quit teaching at Pacific Methodist, joined the faculty of Mills College, and moved the family to Alameda County.[19] The change meant that Zellner shifted from being the only music professor to one of many, and he taught at a school in which music was not considered a vocational choice but rather was treated as though it was as elemental to education as arithmetic or reading. Of the 270 students attending Mills College in 1873, more than 200 of them studied piano and more than 50 studied singing. Along with teaching, Zellner assisted the Musical Society in producing its concerts in the main Seminary Hall.

In the music department at Mills College, Zellner was surrounded by fellow immigrants: “The Germans and Austrians fairly swarmed: Ernest Hartmann, Frederic Katzenbach, Emil Steinle, Otto Linden, Edward Hohfeld, Otto Seyd, and Ferdinand Zellner (who continued well on into Louis Lisser’s time).”[20]

Beutel was director of the music department when Zellner arrived; in 1880, Louis Lisser, trained at the Royal Academy of der Kunst in Berlin, took over the reins of the music department.

The Zellners had five more children while living in Alameda County, four of whom lived to adulthood: Chester born in 1877, Sidney in 1878, Emily in 1882 and Horace in 1886. A son named Gordon was born in 1880 but was not listed among the family members in the 1890 census. The Zellner children grew up in a mixed neighborhood in Brooklyn Township, southeast of Oakland. The Zellners were doing well enough that the family employed a live-in servant, an 18-year-old domestic named Ah Tong. A few families in surrounding neighborhoods also employed domestic help, but the majority were working class families, mixed in a variety of ethnicities. A large community of Chinese, employed in construction of railroad beds for the Central Pacific Railroad, lived nearby. Numerous families living nearby were Portuguese immigrants, many employed in the fishing industry.[21]

Zellner continued to teach at Mills College until 1888. In 1889, the family moved back to Santa Rosa, and he became a professor of music on the faculty of the reorganized Pacific Methodist College. They bought a house at 826 Humboldt Street, about six blocks northeast of the college campus. As the children reached maturity, Chester studied to become an engineer, while Sidney took a job in a local bakery. In 1898, the last of the Zellner childen, Leslie, was born.

Sometime about 1900, Ferdinand and Olive became estranged. At the time, Ferdinand was nearing 70 while Olive was still in her early 40s. Olive moved to Stockton, Calif. The family appeared to break up as well. The elder sons stayed in Santa Rosa and continued to live with their father. Emily married Richard Benjamin Brook in 1904, and they had two daughters, Eudora Elizabeth in 1908 and Rosamond in 1909. By the next decade, they were living in Oakland with Olive, Horace and Leslie.[22]

The earthquake of 1906, best known for the destruction of San Francisco, also leveled much of Santa Rosa, including the main college building and most of downtown Santa Rosa.

Of Ferdinand’s children, Chester became engineer and worked in the waterworks department of the city of Santa Rosa while Sidney continued in the bakery trade. Horace became a brakeman for the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Ferdinand Zellner died of congestive liver failure on July 2, 1919, at Santa Rosa, just two weeks before his 88th birthday. Sidney was still living with him and took care of him in his last years. He was buried in Santa Rosa’s Rural Cemetery, where his first wife, Penelope, had also been buried. His son, Chester, who died in 1932, and his second wife, Olive Jeanette, who died in 1934, are also buried there.

By 1920, Emily and her family moved to San Francisco where her husband, Richard, worked as an electrical engineer for the U.S. Navy. Initially the family rented a flat on Oak Street but bought a house at 127 Fourteenth Street by 1930, just a block from the Presidio. Daughter Eudora Elizabeth, at age 22, had a job as an assistant in an office while Rosamond worked as a commercial artist. Neither of the granddaughters appeared to have married or had children.[23]

Horace also married sometime before 1920, but his wife Jessie was committed to the Agnews State Hospital by 1930, and they didn’t appear to have had any children. Leslie Zellner moved back to Santa Rosa and lived with his brother Sidney. Horace died in 1943; Sidney died in 1950; Emily and Richard died within a year of each other in 1969 and 1968, respectively. Zellner’s granddaughters, Rosamond and Eudora, died in 1964 and 1981, respectively.

Endnotes

[1] Ware, W. Porter and Thaddeus C. Lockard Jr. P.T. Barnum Presents Jenny Lind: The American Tour of the Swedish Nightingale (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1980) 69-72. Numerous modern reports spuriously indicate Lind also performed at the King Opera House in Van Buren, Ark., on the Arkansas River. Lind’s itinerary does not show any stops in Arkansas, much less on the western side of Arkansas. Too, the current King Opera House was not built until the 1880s.

[2] Zodrow, David. “Long Forgotten Song Surfaces,” Northwest Arkansas Times (Fayetteville, December 22, 1974) Section D, 1-2.

[3] Banes, Marian Tebbetts. The Journal of Marian Tebbetts Banes (Fayetteville: Washington County Historical Society, 1977) 81.

[4] Confederate Widow’s Pension Application by Mary Zellner, No. 27023, State Archives. His widow, Mary Polson Zellner, filed for a Confederate widow’s pension in 1925, well after his death in 1911. Her pension application indicated that W.E. Zellner served in Press Carnahan’s company, part of McRae’s Regiment, formally known as the 21st Arkansas Infantry Regiment. The application said he served from 1863 to the end of the war.

[5] Untitled Papers and Slips Belonging in Confederate Compiled Service Records, (National Archives and Records Administration M347)

[6] Banes. The Journal of Marian Tebbetts Banes. 111-121.

[7] Selected Records of the War Department relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, 1861-1865, (National Archives Microfilm Publication M598, Roll 72) p 155, 223; Untitled Papers and Slips Belonging in Confederate Compiled Service Records, (National Archives and Records Administration M347)

[8] Untitled Papers and Slips Belonging in Confederate Compiled Service Records, (National Archives and Records Administration M347)

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Banes. The Journal of Marian Tebbetts Banes. 111-121.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Daily Evening Bulletin, (San Francisco, Calif.: March 8, 1866); Territorial Enterprise (Virginia City, Nevada: March 1, 1866)

[15] Thompson, Robert A. Sonoma County History: Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Sonoma County, California (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1877) 70-92.

[16] Daily Evening Bulletin, (San Francisco, Calif.: December 14, 1872)

[17] Family history indicates Jeremiah Beam was born in 1812 in New York and died in 1880 in Santa Rosa, Calif. Mary Logan was born Aug. 11, 1824, in Wayne, Mo., and died in 1881 in Santa Rosa. The couple had a third child in late 1859 or 1860, according to the 1860 census of Brighton Township, Sacramento County, Calif., but who apparently died prior to the 1870 census.

[18] 1860 U.S. Census, Brighton Township, Sacramento County, California. National Archives and Records Administration. No record of whether the Beams crossed paths with Zellner while in Arkansas has been found so far, although there is about a six-year period in which they might have been in Arkansas at the same time.

[19] 1880 U.S. Census, Alameda County, California. National Archives and Records Administration Publication, T9, Roll 62.

[20] James, Elias Olan. The Story of Cyrus and Susan Mills: a Biography of the Founders of Mills College (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1953) 186.

[21] 1900 U.S. Census, Sonoma County, California, 94.

[22] San Francisco Chronicle. July 12, 1904. Page 12; World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, for Horace Stewart Zellner and Richard Benjamin Brook.

[23] California Death Index, 1940-1997. (Sacramento, Calif.: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Services). All of the Brooks died at San Francisco. Rosamond Brook died Oct. 15, 1964; Richard Brook died Aug. 24, 1968; Emily died a year in July 1969. (The California Death Index put the date of death as July 22, while the Social Security Death Index put the date at July 15.) Eudora died on Oct. 7, 1981. Horace Zellner died Dec. 22, 1943, and his wife, Jessie, died Nov. 22, 1966, at the Agnews State Hospital. Sidney Zellner died June 7, 1950.