There is not a closer association between a fabled beast and a mythic people in the whole of America than between the wild razorback hog and its Arkansawyers. The razorback is the only animal that plays so well into the Arkansaw stereotypes, both those cherished by Arkansawyers about themselves and those meant as derogatory quips by people from beyond the borders of Arkansas. On the positive side, the Arkansas razorback is cast as self-sufficient, clever, quick of foot, fierce when backed into a corner, and deeper in American pedigree than the Mayflower pilgrims. Its less savory qualities, so to speak, are that it has a voracious, unquenchable appetite, it steals the crops out from under its neighbors, and it is lazy. These are the qualities that surrounded the razorback and its Arkansawyers at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, but they were not always thus.

The word “razorback” did not start out as a conjoined suffix to “Arkansas” much less as a reference to hogs. During the early 19th century, the term was used almost exclusively for the razorback whale, Balænoptera physalus, better known as the finback or rorqual whale. Later the term began to be applied to any animal with a pronounced spine, such as gaunt horses and bowed-up bovine. Meanwhile, during the early part of the 19th century, feral hogs of the South were more often referred to as “alligators,” “tonawandas,” “land sharks,” or “land pikes.” The earliest known reference to a feral hog as a “razorback” came in 1843: A correspondent to The American Agriculturist reported his success at using beets as feed stock for his breeding sows and store hogs, but he warned that “a Berkshire will get fat where a razor-back would starve.” The correspondent made no attempt to explain what he meant by the word “razor-back”; he clearly thought that “razor-back” would be widely understood by the reading audience and that readers would also understand that razorbacks do not easily gain weight.

When the Writers Program of the Works Progress Administration put together a book about Arkansas during the Depression, one of the writers offered a supposition for how “razorback” came to refer to hogs:

Like all true folk-myths, the razorback stories have an unknown origin. Assume that someone commented on a temporary scarcity of acorns and the consequent thinness of his hogs. A second man would agree, saying that his sows were able for the first time to squeeze through the garden gate. A third would testify that he could now hang his hat on the hips of his hogs. The next would aver that his swine had to stand up twice in order to cast a shadow. One man was almost bound to swear that his hogs were so desperately starved he could clasp one like a straight razor and shave with the bony ridge of its back.

This explanation, although it might not be too far off the mark, does little to suggest why the razorback ended up tied to Arkansas. Folklore across the South maintained that the woodland razorback was the descendant of European hogs brought to North America by Hernando de Soto during his ill-fated search for gold, starting in Florida and meandering across the south, through the present-day states of Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas, where he arrived in the spring of 1541.

Writer Bob Lancaster turned a skeptical eye toward this claim of porcine proliferation in 1986 for the Arkansas Times and searched through the reports from DeSoto’s expedition for evidence. Lancaster noted that reputable historians had discounted the story of hogs, primarily by ignoring it, but he concluded that the reports indicated that European pigs occasionally had indeed escaped from DeSoto’s large droves. One report indicated that DeSoto’s men came across an escaped sow that had recently dropped a litter of 13 pigs. “So there it is,” Lancaster wrote. “If the cavaliers had backtracked more often, they undoubtedly would have found this scene repeated many times — ancestors of the razorback scattered throughout the South, with no natural enemies to speak of and no shortage of acorns — with nothing finally to check their proliferation and prosperity until the vast land-clearing and extensive hunting of the modern age.”

To be fair, John Gould Fletcher mentions DeSoto’s hogs in his history, Arkansas, describing the winter when the expedition bogged down in Arkansas: “Here they eked out their lives on the corn, beans, pecans, and dried persimmons provided unwillingly by the Indians — a diet varied mainly by rabbits, which the savages had taught the Spaniards to catch in snares. There numbers were much reduced — about three hundred and forty Spaniards and a pitiful lot of some forty unshod, scarecrow horses alone remaining. At this time, or perhaps earlier, their drove of hogs took to the woods — to provide respectable ancestry for the Arkansas razorback of later years.”

The truth of whether the razorback is a descendant of DeSoto’s pigs is less important here than the fact that Arkansawyers enjoy the notion that these wild hogs of the woodland are descended from the stock of a conquistador and that their ancestral porcine progenitors had been roaming the Arkansas hinterlands some 66 years before the advent of Jamestown and nearly 80 years before the arrival of the Mayflower. It provides a sharp rebuke to New Englanders or East Coasters who want to claim that their history is somehow longer or deeper than that of Arkansas if one can cite the rangy razorback forebears that got to the New World prior to some Yankee’s great-granpappy.

Initially, jokes about the razorback were simply a poke at the animal itself and might be as easily applied to the feral hog of Alabama as the razorback of Arkansas. Perhaps the simple euphony of combining the word “Arkansas” with “razorback” was enough to bring the jokes to rest on what previously had been the Bear State. Perhaps the enormous growth of swine production in Arkansas played its part. By 1840, Arkansas had about 400,000 head swine, according to the U.S. Census, the highest number in the country per capita. By 1860 the number of swine in Arkansas had nearly tripled.

Early efforts to make fun of the razorback hog had no attachment to Arkansas. The jokesters were simply poking fun at a funny animal. Boyce House, a Texan, told the tall tale of a razorback hog that “ate a stick of dynamite, blew up, broke all the windows in the house, wrecked the barn, killed two mules, and was a mighty sick hog.” Another writer endeavored to give a pseudo-scientific description of the animal:

Arkansas has a greater variety of hogs and less pork and lard than any State in the Union. An average hog in Arkansas weighs about fourteen pounds dressed with its head on and about six pounds and a half with its head off. It can outrun a greyhound, jump a rail fence, climb like a parrot and live on grass, roots and rabbit tracks. It hasn’t much tail nor bristle, but plenty of gall. It will lick a wolf or bear in a fair fight. … It can drink milk out of a quart jar on account of its long, thin head. This type of razorback is known as the stone hog, because its head is so heavy and its nose so long that it balances up behind. The owner of this type of hogs usually ties a stone to its tail to keep it from overbalancing and breaking its neck while running.

Arkansas writer Charlie May Simon boiled the descriptions down to their essence when she wrote a children’s book in which razorbacks played the antagonists:

“Many a man would rather see a panther or a wildcat hanging around his farm than a herd of Arkansas razorback hogs. Lean, lanky, and hungry all the time, they could outeat any animal that ever lived, and they still didn’t weigh enough to leave their footprints where they walked. Their snouts were as long as walking sticks, and their backs as sharp as razors. They were so thin it took two of them standing together to cast a shadow. If one was by himself, he’d have to stand up twice.”

Any animal or person compared unfavorably to a razorback was in a sad state of affairs. On the eastern seaboard, the razorback hog was often referred to as a “Carolina racehorse,” which said less about feral pigs than it did about the quality of racehorses in the Carolinas.

Even when writers were not intending comic relief, their stories could give way to stereotypes of the razorback: “Breed is not everything, as is evidenced by the fact that a carload of fatted Arkansas razorback hogs sold in Chicago the last week in July at $5.80 per hundredweight. Whether the feeder finished them at a profit is not known.” The razorback must be either too rawboned to sell at market or if fattened enough to sell must have cost a rump and a hock worth of feed to bring to market condition.

As train travel brought more people through Arkansas, though, descriptions of the state were invariably linked to the razorback. A traveler from Kansas City caught the spirit of things: “We were curious to know just what this State was that we had reached, … which man had so neglected; but not until there loomed in view that historical anmal [sic] with its long nose and razor back were we assured we were travelers in Arkansas.”

Another traveler, Dr. W. S. Caldwell, wrote to his hometown newspaper about his journey through the “Land of Cotton” and his first encounter with a razorback hog. The newspaper’s subhead tells most of the story: “‘Razor-Back Hogs’ seem to Have a Monopoly on the Ambition in Arkansas —The People Indolent and Shiftless.” Caldwell wrote:

“Early in the forenoon we reached Little Rock where I saw the first razor-backed Arkansas hog, who roamed the street at his own free will and seemed to have the same rights upon the sidewalks as his two-legged companions. … The only living being that I saw all day that seemed to have a move on him was this razor-back hog. He rooted in the ground with an energy that showed that his environments had not paralyzed his energies and made him the lazy shiftless being that his two legged fellow citizen seemed to be.”

By the end of the 19th century, the razorback was no longer the butt of the joke but often the measure of disdain. A newspaper editor in Sandia, Kansas, for instance, looked for every measure of condescension he could find to describe a rival editor at the Junction City Sentinel:

“For over two long years he has been like a festering sore, a leech, a vampire or fungus, absorbing life blood from the body politic, giving no good in return but acting as a poison ivy vine upon the tree supporting it. … He endeavors to pay his bills about as much as the devil works to save lost souls. He is absolutely without good principles. He does not look men in the face but hangs his head like a brute. His heart is as black with gratitude as the heart of a Spaniard. … His mind is as pure and his brain of the quality of a putrescent cabbage. … If he had been created a dog he would be a cowardly, sneaking, snapping yellow cur with his tail between his legs. If he had been created a hog he would be an Arkansas razorback.”

The low point may have come in the 1890s when members of the Georgia bar began using the term “razor-back” derogatorily to refer to colleagues “who make a living by inciting actions of tort growing out of personal injuries, especially against larger corporations.” Today, they might be referred to as ambulance-chasers, but in 1894, W.L. Granberry wrote of these razor-back lawyers: “The name at once commends itself, because of its fitness, in describing the class of practice-hunting lawyers. Their energy, their hunger never satisfied, their disregard for the rights of others, are well typified in the family ‘razor-back,’ which no fence ever turned and no corn-field every fattened.”

Lawyers indeed.

During the first decade of the 20th century, the jokes deriding Arkansas and razorbacks were about to come to an end. Like other minority populations that become saddled with an offensive, derogatory term, Arkansawyers took hold of the “razorback” sobriquet and didn’t let go. They embraced the razorback and made it a badge of honor. Like so many progressive movements, this one began with students at the University of Arkansas.

The university’s original mascot, the Cardinal, was adopted during the late 1890s, but it had been chosen partly by default. When students chose the school colors in 1895, they voted for cardinal. The other option was heliotrope, so cardinal was perhaps a foregone conclusion. Athletic teams were just then being organized, and so the Cardinal was a natural choice for the team’s mascot. Likewise, the yearbook, which began publication in 1894, was also titled the Cardinal.

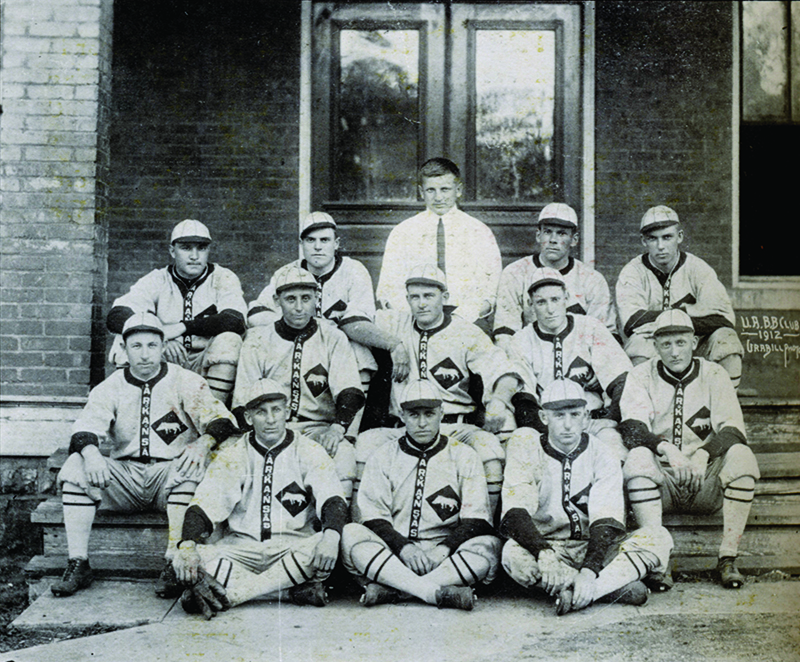

The Cardinal lasted until 1909. In that year, the University of Arkansas football team went undefeated, led by the university’s first full-time coach, Hugo Bezdek. The team thrashed regional powerhouses such as the University of Oklahoma and Louisiana State University. Half-way through the season, the University of Mississippi team was so cowed that they sent a telegram to Bezdek to say they would forfeit their game rather than come to Fayetteville as planned.

According to popular legend, after the late-season game with LSU, coach Bezdek told a crowd of fans and supporters that his boys had played “like a wild band of razorback hogs.” The crowd liked the sound of that and understood the inherent traits of the razorback: lean, fast, ferocious; so, soon the razorback was the newly adopted mascot, so the legend goes.

Truth be told, though, students had started referring to the team as the “razorbacks” in print as early as 1907, a year before Bezdek came to coach at Arkansas, and they were frequently called the razorbacks in stories and headlines throughout the 1909 season, well before the LSU game. One of the players from that storied team, Phil Huntley, who played center but arrived at school prior to Bezdek, talked to a sports writer many years later and recalled that he and the team, his fellow Arkansas travelers, had taken a slow train through Texas to play a game. After arriving in Dallas, they got off to stretch their legs. Huntley recalled: “Somebody said, ‘Here come those razorbacks.’ See there were a lot of jokes about Arkansas back then.’”

No doubt, though, that Bezdek is the person who popularized the term. By 1910 the athletic teams had made the transition from the Cardinal to the Razorback, and by 1913 Edwin Douglass had written the words for a new fight song that included “razorback” as part of its lyrics. In the school year of 1915-16, editors of the student yearbook, still titled the Cardinal, decided to change its name to reflect the ascendancy of the Razorback as mascot. One of the assistant editors at the time, Jim Trimble, recalled that the change to Razorback created a furor on campus between detractors and supporters with opposition rooted in the derogatory connotations associated with “razorback.” A similar debate occurred when the student newspaper at the university changed its name to The Arkansas Traveler, another phrase of mixed emotional appeal, but the student editor wrote in defense of the name Arkansas Traveler:

“The present name, although almost unanimously selected by the students in the name contest has been criticized by students, faculty members and by town people.

“It is not difficult to understand why some should see disgrace written in the name made famous by Opie Reed and why others should object so strongly to a reminiscent of frontier days. The students are urged to get away from the idea that razorbacks and travelers are worthy of the dignity attached to their name. The ridiculous application of rural wit to the name of a great state has been discontinued, almost forgotten and only serves to remind people of the unscholarly attainments of previous generations. …

“The citizens of Arkansas have no cause to be humiliated when the name Arkansas Traveler is mentioned in their presence.”

Even as the “rural wit” declined, so also did the number of real razorback hogs, and domestic hogs in general, dwindled in the woodlands of Arkansas and the farms of the South during the first half of the 20th century. In 1967, free-ranging hogs were banned from the national forests, and by the 1970s, domestic hog production in Arkansas had fallen back to what it had been in 1840.

As if to make the point, students in 1936 went scouring the countryside to find a live razorback pig to bring to one of the football games. A similar effort a half dozen years earlier had to rely on importation of a feral hog from Louisiana. In 1936, though, the students found a southern Arkansas farm with feral hogs and shipped one of the hogs to Fayetteville by rail in time for the game. The students christened the Arkansas razorback with the name “Traveler” and the student newspaper reported the details:

“Traveler” came from John Clark Riley’s grandfather’s farm, where he had 1,500 of them running wild in a stretch of woods 30 miles long in southeast Arkansas.

Staff members send a wire to the Hamburg farm and get a reply: “TOO LATE TO GET HOG STOP SORRY.” It’s signed “Shorty.”

Riley phones Shorty, who turns out to be the foreman of the farm, and convinces him to capture one of the hogs and ship it to Fayetteville. Shorty explains why that will be difficult: “These Razorbacks just roam wild, you know, and they’re kind of hard to get to. You’ve got to lasso ’em from a horse. But we got plenty — once we shipped out 27 carloads at a time.”

Throughout the early 20th century, Arkansas writers repeatedly reported that the real live razorback was extinct, and with the 1964 football season, jokes about Razorbacks also came to an end. Football coach Frank Broyles, like a modern Circe, turned nearly every Arkansas man, woman and child into a hog when his team went undefeated and claimed the national championship, notwithstanding the Associated Press. Within a decade, the Razorback was celebrated across the state in all manner of form, from hog hats to license plates, from high art to bobbles and trinkets, from hundreds of porcine-named restaurants to hundreds of thousands of T-shirts.

An alumnus who grew up in the Delta of Arkansas recalled the time in the 1960s when his family stopped for dinner at a restaurant in Jonesboro. On the table were little packets of sugar for the ice tea. Printed on each packet were a picture of the Razorback mascot and the words “Talk Up Arkansas.” No longer was the feral hog a symbol of opprobrium. Rather the razorback had become the standard for expressing pride in Arkansas, not just its university, not just its football team, but its entire state.

Research for this story was done for a presentation at the Historic Statehouse Museum in Little Rock, Arkansas, and the first version of the written story was printed in Arkansas magazine.